Blog Archives

How D-Day’s Success Was More Than Just a Beach Assault

The most complicated and multifaceted project in human history was not the moon landing, but a seaborne invasion that took place 80 years ago. On June 6th, we commemorate the single most significant event of WWII. Had D-Day not taken place, or even worse, been a failure, as it could so very easily have been, Russia’s advance on the eastern front would have been brought to an abrupt halt.

For D-Day, there was only a narrow window of opportunity—what with tide and weather—that had it not made it when it did, Hitler would have known that his ‘Atlantic Wall’ could not have been assaulted until the following year. In that event, he would have felt free to withdraw massive forces from the western theatre and direct them to reinforce the eastern front. Had D-Day been activated and failed—a la the Dieppe Raid—he could have withdrawn even more forces and begun the process of throwing Stalin’s Red Army back, very possibly to its starting line, which would have left Hitler in control of almost all of European Russia. At that point, and contrary to what he had promised the Allies, he would almost certainly have sought a separate peace, so pulverised, depleted, and shorn of infrastructure was Russia.

For our part, we would have been left, along with our American allies, to fight on alone. Victory would still have been ours and, ironically, with nothing like the bloodletting that actually took place in the eleven months that followed D-Day. Little realised is the fact that in those eleven months following D-Day and peace in Europe, more lives were lost than in the preceding five years of war. Allied victory in Europe would have come not in May 1945 but in August had we been forced back onto our island following defeat on the beaches nor ever left it because we had missed that window. Hitler’s Reich would have ended that August not by British and American foot soldiers, but by the atom bomb. Not generally realised is that the atom bomb was first intended for use against Germany. We and the Americans had always had the ‘Germany first’ policy for whose defeat we would prioritise. It was only because D-Day was a success, with the bomb not deployable until August, that Hitler’s Reich was spared the horror that descended on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Some have argued that it would have been better if we and the Americans had sat back on our impregnable island, described at the time as ‘an unsinkable aircraft carrier’, and awaited the results of that first test in the New Mexican desert. Once in possession of the bomb, it was game over for any who opposed us. Germany would have received what the unfortunate Japanese received later. The Japanese, who had already put out peace feelers, would have seen what happened to Germany and rushed to avoid the same fate. As it was, they were left firmly believing, as many do to this day, that it was only used against them because they were Asians.

It is a fact that in terms of lives saved, civilian and military, the bomb’s deployment against Germany would have saved millions, as well as eastern Europe from forty years of misery and death from Soviet occupation. Cities and infrastructure would also have been saved. Of course, the great imponderable, while we sat it out for a year and awaited developments, was would it work. But the leading physicists involved in the Manhattan Project were confident it would work.

It is doubtful if humans will ever again put together so massive, complex, and costly a war operation as D-Day. The Apollo landings on the moon pale before it. Hitler was convinced to the end that the landing would fall on the Pas de Calais area. Why? Because an incredible deception was worked on him. He believed that although it was heavily defended, it was the shortest route, had plentiful harbours, and was the closest to Germany. He also believed that, short of defeating his enemy on the beaches, victory would go to whoever could get the most munitions and sinews of war to the combat zone quickest. Because he had trains and roads, he reckoned he could beat a water-reliant adversary. When he looked further down the coast, the seaborne crossing was four times as great and Normandy, in particular, had next to no ports.

Little did he know that the genius boffins working for the Allies had come up with a perfectly viable way to build a concrete harbour and tow it across the channel. It was code-named Mulberry. Then there was what seemed like the insurmountable problem of getting millions upon millions of litres of fuel for the thousands of tanks and other vehicles needed. Again, the boffins set to work. They came up with Pluto—Pipeline Under The Ocean—something that had never been done before. And they laid that under the very noses of the Germans.

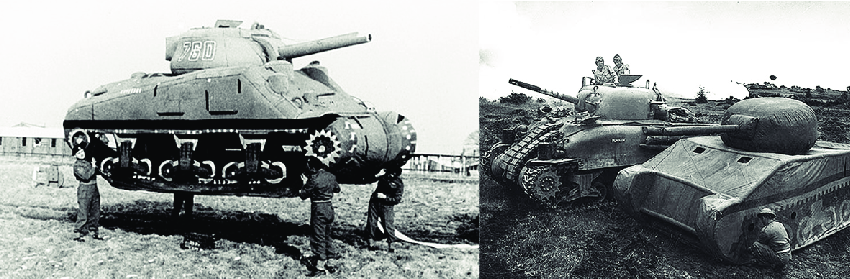

Then came, perhaps, the most dazzling part of the Allied deception: they stationed an entire army of tanks, military vehicles, and aircraft all over Kent, the county facing the Pas de Calais. Except that they were never going to threaten Hitler’s Reich. They were beautifully crafted inflatable dummies. Seen by reconnaissance aircraft, they were totally convincing. Strutting around this mighty conglomeration of men and material was the Allies’ most aggressive and successful general, George S. Patton. Surely this had to be the clincher for Hitler!

A necessary action the Allies had to take, but yet one still rich in deception, was to paralyse German troop movements towards Normandy by bombing roads, marshalling yards, and rail networks. An incredible tonnage of high explosives rained down on the dukedom of the man who had changed England forever by launching his own invasion in 1066—only that time the invasion was the other way round. However, an equal if not greater tonnage was dropped on the Pas de Calais area. There was so much more that an entire volume would be needed to cover it.

Thus it was that Hitler remained convinced it would be the short route. For forty-eight precious hours after the dawn landings, he held back his armoured divisions, believing Normandy was a feint. Told that 150,000 men with accompanying armour and war material had been put ashore on day one alone and that over 5,000 naval vessels lay off the Normandy coast, he still held to his view. That goes a long way to explaining why the Allies had turned against the idea of having Hitler assassinated; he was, in Lenin’s term, the most ‘useful idiot’ of them all.

During that fateful lead-up to that most extraordinary of days on the 6th of June 1944, not a single leak of Operation Overlord’s true landing area reached the Germans. Almost three hundred miles of southern England stretching from Dover to Land’s End was little more than an armed camp, yet still the secret held. That, perhaps, is the most amazing thing of all as we salute the 80th anniversary of the storming of those beaches and those few magnificent heroes who are still with us today.

The bomb saved us all

Though a quarter of a million Japanese would have to be sacrificed in the initial blast and its aftermath, it has been estimated that perhaps eight times that number would have perished on both sides before Japan could have been overcome by conventional means.

Amidst all the ballyhoo of this incredible election we are in danger of not giving proper thought to an event which has shaped all our lives. Seventy years ago today saw an end to what Churchill called ‘the German War’. It was a war in which 50 million died – 20 million, let us never forget, Russian.

I have never regarded the Second World War as anything other than a continuation of the First, but with a 21-year interregnum. On 8th May 1945 the world was still far from at peace. Not yet vanquished were the fanatical Japanese. If our soldiers feared the last ditch fanaticism of the Nazis as they stormed across the Rhine into the enemy heartland, their fears were multiplied several fold as they considered the horrors of what awaited them on the beaches of Japan. Their naval comrades had already experienced a foretaste of what they could expect with the Kamikaze death flights into their ships.

As the great armies of the Western allies celebrated with their Russian allies in the West, they knew that an even more fearful test of their resolve awaited them in the East. Bloodletting on a scale hitherto unknown seemed guaranteed as they briefly enjoyed their moment of triumph in Europe before their embarkation to the other side of the world and a fresh clash of arms.

Their foe in this encounter did not abide by Western concepts of warfare and could, especially in defending their homeland, be expected to die to the last man and perhaps even woman. At that very moment, while the celebrations were continuing, British Empire forces were locked in mortal combat in the steaming jungles of Burma and south east Asia while their American allies were island-hopping ever closer in the Pacific to the Japanese mainland.

But far away in the deserts of New Mexico a secret project was being furiously fast tracked to its terrifying completion. It was a bomb of such enormous potential that a single one could lay waste an entire city. Millions of lesser bombs had fallen on the cities of the Reich, but still there were whole districts of them relatively unscathed. If it worked then even the suicidal Japanese – who at that moment were preparing for a ‘twilight of the gods’ – would bear what their emperor would later broadcast ‘the unbearable’ and surrender, rather than see their 2000-year-old civilisation wiped from the face of the earth.

In all the long march of humankind towards a better world, the stakes had never been higher. Terrible as the new weapon was, it would save those fearful young Western men who were even then preparing to board their ships, as it would also, ironically, save the Japanese themselves. (Though a quarter of a million of them would have to be sacrificed in the initial blast and its aftermath, it has been estimated that perhaps eight times that number would have perished on both sides before Japan could have been overcome by conventional means.) So while we are right to commemorate the end of the war in Europe, we must not forget the true end of the war, three month later.

This ‘true end’, as I call it has, in my view, the greater significance. This is because it really did achieve what many had, mistakenly, believed in the First World War to be: ‘The War to End Wars’. From the detonation of those two nuclear devices over Hiroshima and Nagasaki came a belief – rightly – that global war was no longer an option as it would escalate, inevitably, into a nuclear conflagration and with that the end of all human civilisation. In such a scenario there could be no winners and it is my belief that that it is this appreciation during the Cold War that kept it from becoming a hot one.

As for the reason I do not believe the two European wars to be separate wars, it is because certain powerful elements in Germany considered the outcome of the First World War unfinished business. It took only a charismatic demagogue like Hitler to fan the embers for a re-run. Even then it would have been unlikely to happen, but for the Wall Street Crash and the impoverishment and mass unemployment which struck Germany. Of all the advanced economies, Germany suffered by far the worst because its situation was dramatically worsened by the huge reparations it was forced to pay under the Versailles treaty.

Why those powerful elements in Germany considered the war unfinished business was because the Western allies did not press home their advantage when they finally broke the four-year impasse on the Western Front and went on to smash the, by then, retreating German army which was surrendering in droves. Heeding Ludendorff, the German commander – who had a breakdown – and his call for a cessation of hostilities (Armistice) the allies allowed the Kaiser’s high command to maintain the fiction that it had not been defeated in the field. Hitler, of course, was all too ready to encourage them in this misplaced belief and, more to the point, provide them with the tools to try once more. The rest is history.