Category Archives: society

Brexit and Beyond: Uniting the Old Commonwealth

On the seventh anniversary of Brexit, it is both disheartening and exasperating that the project remains shrouded in negativity, with scant attention paid to the opportunities it presents. A dazzling prospect lies in wait for the British government. By overwhelming majorities, the citizens of our erstwhile Commonwealth allies – Canada, Australia, and New Zealand – have signalled their wish for a revival of the kinship that united us at the dawn of the 20th century.

While steadfastly maintaining their sovereign parliaments, these nations envision sharing with us a common defence, security, and foreign policy. They also aspire to enable freedom of movement, commerce, recognition of qualifications, and much more. This collective interest embodies a potential union that could function exceptionally well. Our levels of employment and standard of living are broadly comparable, and almost all aspects of our societal framework; our values, culture, history, parliamentary system, law and language, are remarkably similar. If realised, this would form the largest union globally, and provide a sturdy pillar of support to a beleaguered Uncle Sam.

Objectively, such an endeavour could be considered a straightforward decision and one that should draw cross-party backing. So, why does Westminster hesitate to seize this momentous opportunity? Could Brexit yield a more significant dividend than to reunite our familial ties in such a monumental development? The renewal of this close relationship, now known as CANZUK, holds a promising future.

The emerging power of the CANZUK union

Democracy and our Western way of life are currently in crisis. The rise of a militarised China, a crazed and delinquent Russia, and increasing numbers of authoritarian states pose what some see as an existential threat to our Western values. Yet, a powerful development could potentially reverse this situation.

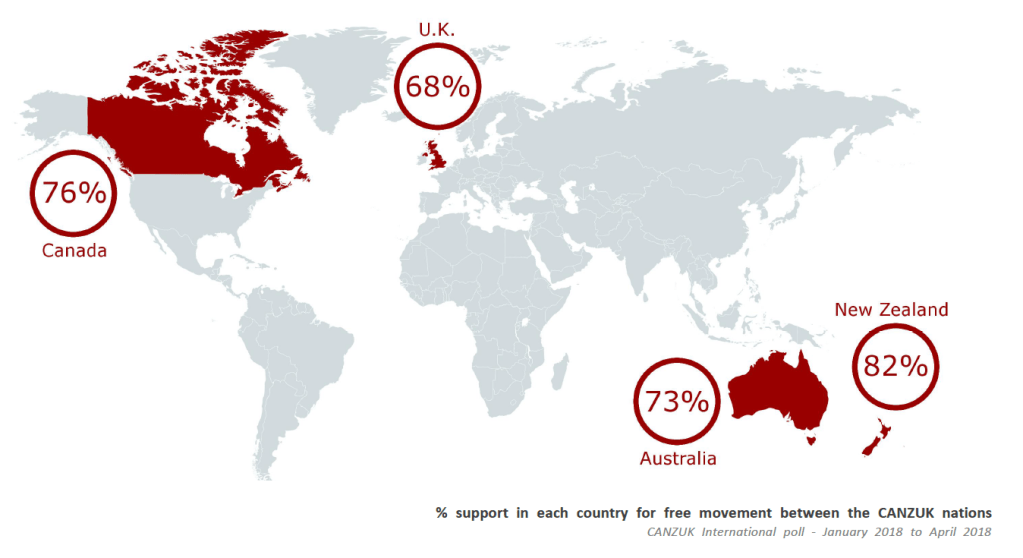

Forces are gathering for a union of four pivotal democracies – an entity known as CANZUK, an acronym for Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. Public polling indicates broad support: 68% in Britain, 73% in Australia, 76% in Canada, and 82% in New Zealand. Each nation will remain sovereign, yet they’ll cooperate in foreign policy, defence, freedom of movement and trade, recognition of qualifications, and sharing of security concerns—an existing example of such cooperation being the Five Eyes Agreement, which also includes the United States.

In terms of land area, this proposed union would be larger than Russia, boasting a combined GDP of $6.5 trillion and a population of 135 million. Its military budget would exceed $100 billion, making it the third largest in the world.

While many draw parallels between CANZUK and the EU, crucial differences exist. The CANZUK nations share a common language, heritage, and lifestyle. Their standard of living, employment levels, and political institutions run in parallel. Critics of CANZUK have termed it ‘a white man’s club’, but CANZUK International, the organisation advocating for the union, has stressed that the door will remain open to other like-minded nations sharing the same values, including India.

Historically, the CANZUK countries have fought together in defence of freedom, never against each other – unlike the turbulent history of European nations. Another critical difference with the EU is that no CANZUK nation will impose rules and regulations on another, unlike the centralised control from Brussels.

The emergence of the CANZUK union could reinvigorate global leadership, inspire the United States to remain globally engaged, and establish a third significant pillar of Western values alongside the US and EU.

Each CANZUK nation will also gain unique benefits. Canada could negotiate on more equal terms without the overshadowing presence of its giant neighbour. Australia and New Zealand could face China’s assertiveness more confidently, and Britain, once history’s largest empire, would regain its international influence and join the largest confederation on the planet – a reinvigoration sparked by Brexit during its dire straits.

The prosperity of CANZUK members could significantly increase as a result of this union. Critics who question the viability of trade due to geographical distances overlook the success of global trading giants like China and Japan. Advancements in AI and green technology, like the US Navy’s move towards virtually crewless ships, are likely to reduce shipping costs in the future, making the trading prospects even more favourable.

But perhaps the greatest beneficiaries of this promising development will be the young. They would be free to live, travel, study, and work across the expansive regions of CANZUK. Even retirees could benefit from the freedom to relocate. This exciting prospect is, to borrow a popular phrase, ‘a no-brainer.’ It should be for us grown-ups too.

The rise of the CANZUK union could potentially reinvigorate global leadership, inspire the United States to remain globally engaged, and establish a third significant pillar of Western values alongside the US and EU.

While Brexit initially represented a step away from supranational involvement for Britain, it may have ultimately set the stage for a stronger, more aligned union with countries that share deep historical and cultural ties. The post-Brexit era for Britain may not be one of isolation, but of renewed global influence and connectivity.

Many didn’t think Britain had much of a future outside the EU, but the world has always been our oyster. The CANZUK proposal is just one way we’re demonstrating that. Even domestically, we may find a solution to the aspirations of our member nations of the UK. As federal states within the union, they too could at last stand proud as sovereign states.

The notion of poor, tortured Ireland reuniting and choosing to join this new brotherhood of nations is not beyond the realms of possibility. This would be a testament to the appeal and potential of CANZUK, its promise of mutual benefit, and its respect for national sovereignty.

This is not a mere dream; it’s a potential reality within our grasp. It’s time to seize the opportunity and make CANZUK a part of our shared destiny. In an era marked by uncertainty and rapid change, the promise of CANZUK is a beacon of stability and shared prosperity, a testament to what nations can achieve when they unite under common values and a shared vision. Let’s look towards this future with hope and determination.

Only an intelligent and proactive response to the root causes of knife crime will work

Once regarded as an exemplar of decency and civilised living, parents in suburbs of Britain’s capital now fear for the lives of their children going out to meet their peers or even popping down to the nearest corner shop.

Week after week, the stabbings continue. Violent death stalks the young of our cities like a bacillus ready to strike at random. It is amazing that we have stood back and watched this wretched tide of misery rise with almost a detached equanimity. But something happened a few days ago which seemed to shake us out of our torpor. Last week, in quick succession, two seventeen dear old white children – a girl and a boy – died.

It is a terrible thing to suggest, but I believe society gave every impression of not wanting to over-exercise its concerns because the killings have very largely been confined to the non-white community. It was black on black, and mainly part of a gang culture which had developed. How mortifying that must seem to the families of all those other kids who have died to hear the alarm bells suddenly ring and note the attention which the two recent deaths have attracted. Were their children not as worthy of equal attention?

I do not think it fanciful to suggest that if this epidemic of stabbings were happening to white children, the army would be on the streets by now.

There was an echo in all this of the working class public’s justified rage at the efforts and astronomic sums dedicated to the search for the high profile and professional class’s child, Madeline McCann. Were their children not also going missing? Why was Madeline so special? And where was the fairness in a system that only took notice and opened its purse-strings when it happened to the favoured ones in society.

Now that the wider public have finally woken up to what is happening in its cities, we have to pose the question: what is to be done? First, we have to identify the drivers of knife crime. There is no single cause – there seldom ever is – but in my book, lack of prospects must feature highly. Any youngster not benefiting from a stable family life, a decent education and challenging/enjoyable extracurricular activities is fodder for the gang leaders.

No single factor contributes more to a youngster going off the rails than the lack of a father figure in family life. And no community in the country suffers more from this of this than people of Caribbean ethnicity. Sadly, people in this community are the very ones hardest hit by the killings.

If you do not accept this argument about the importance of a father figure, ask yourself this question: how many Jewish mothers are left to get on with it because papa has done a runner? And when was the last time you heard of a Jewish boy being arraigned in court for a knifing, or indeed for any anti-social activity? That is because family life is so cohesive and all-embracing. You could almost say suffocating. The sheer shame of letting down not just your family but your community is enough.

When there is a father figure, why doesn’t dad do his own Stop and Search before his boy steps out on to the street? I know that if I lived in one of the affected areas, I couldn’t live with the thought that my boy might be armed and dangerous. I would have to satisfy myself.

Then there is the matter of policing the streets. If a cast iron assurance were to be extracted from every one of the forty-three constabularies in England and Wales that those twenty thousand cuts in police numbers would be reinstated on condition that every last one went into front line service, we could expect something quite dramatic. Even the peddling of drugs would take a severe hammering. The new officers swamping the streets would come to be seen as the nation’s protectors. They could be expected in their role to accumulate from a grateful populace veritable mountains of evidence as to where the baddies were hanging out. When arrests came, they should be processed in double quick time instead of the hours each arraignment presently takes. That in itself puts a lot of officers off making arrests.

Then we must reinstate the youth clubs and all the related facilities, which were so ubiquitous in former times. When a young person at a loose end leaves the house knowing that his mates are just down the road at the youth club, rather than hanging about on the street corner, he is much less likely to see someone he can pick a fight with to impress his peers.

Of course, so much of the downward spiral begins with school exclusions. While a disruptive pupil cannot be allowed to erode the life chances of his classmates, equally he must not feel that society has washed its hands of him, like in so many cases the father has. Funds must be made available to schools to manage such pupils in a positive and inclusive way. Being chucked out of school and bumping into classmates on the streets later is almost certain to foster a burning resentment that can only lead to trouble, as well as humiliation, for the one that society regarded as a reject. If he cannot gain acceptance anywhere, he will seek it from the last redoubt of what we unkindly regard as the loser: the gang. There he will set about burnishing his credentials by doing something dramatic. A killing in that world would do very nicely. One way or another, a young person will seek the respect of their peers, even if has to be gained at the point of a knife.

What is needed on the part of society is an intelligent and proactive response to all the issues. Compassion for what has gone wrong in the lives of the perpetrators should lie at the heart of it.

Little Harbour is childcare at its finest

Grant has been visiting Little Harbour to teach Jacqui Sweet, Activities Co-ordinator, and children like Jake how to use their new 3D printer.

I recently visited the Little Harbour Children’s Hospice in Cornwall with my son, Grant, who has been giving his own time on weekends to teach staff and children how to use their new 3D printer.

Having spent my own childhood in care at the Foundling Hospital in more disciplinarian times, it was wonderful to see a real-life example of how childcare should be delivered. Unlike the children of my institution, who enjoyed good health in the main, tragically all of the young people passing through Little Harbour’s doors are afflicted with a range of life-limiting conditions. However, thanks to the love and dedication of the staff there, and the truly wonderful facilities and activities made available, these unfortunate children are enabled to live to the absolute full within the limitations of their conditions. The loving staff provide stimulating activities and organise daytrips for the children, and parents are able to stay there too for respite.

Little Harbour, along with many other children’s hospices, benefits from no state funding. The whole operation depends entirely on the generosity of members of the public. This generosity began at Little Harbour with a farmer who donated several of his precious acres to the cause of enhancing life-limited children’s quality of life.

I will be following this blog post up with a more in-depth look at the very fine work that takes place at Little Harbour, made possible by its many benefactors. In the meantime, if you are contemplating donating to a worthwhile cause, you really could do no better than Children’s Hospice South West.

Gay schools aren’t the answer

If you remove certain sections of society from the mainstream you risk encouraging the majority to believe that they really don’t want to belong to the mainstream.

I was taken aback recently to learn of a serious proposal to set up a school for Gays. While a firm supporter of not stigmatising minorities – as a child of an unmarried mother at a time such things were scandalous, I know just what that means – I felt that this was simply a bridge too far. In fact I believe it could be counter-productive, harming the very people it was designed to protect; a classic case of the law of unintended consequences. Humans across the world belong to a single family. If you remove certain sections of society from the mainstream and create an environment in which they circulate for substantial and formative periods only among people of their own preferences you risk encouraging the majority to believe that they really don’t want to belong to the mainstream. We know the aims of Gays in making this proposal are laudable; they wish to experience and benefit from an education free from the slings and arrows of a taunting minority. But the answer, I fear, is not to remove them from the orbit of the bullies but to bear down and educate bullies into accepting that it is they – the bully – not their victim, who is the problem. It was never more clear to me than during my army service in Northern Ireland that if people are ghettoed from their fellows they will not relate to them and, as a consequence, would be capable of doing terrible things. And there, job discrimination was total – in schools, churches, policing, pubs, town halls, housing and just about anything else you could think of. The first question that any employer asked of you was, “are you Catholic or Protestant?” We saw in blood where that led.

Social attitudes can be turned full circle. We know this from things we have already achieved. Do you remember that ‘Carry On’ film in which a partying group of young medics came out and piled into an open-topped sports car and roared off? The noisy, raucous group were all the worse for drink. We thought, at the time, it very funny and so did the producer. Neither he nor we would think that now. In fact we are appalled that we ever thought it so. In similar vein was the ubiquitous glamorising of smoking on the silver screen. Also, look at our previous indifference to the disabled; we never bothered to put wheelchair access into anything. Then, just let a landlord – as happened when I first lived and worked in London – try putting in his window a sign reading ‘No Blacks, Irish or Dogs’. All hell would break loose. Women’s prospects have improved immeasurably from what they were and so have peoples’ of other races. I could go on. Indeed, some might argue that in today’s Britain your life chances might be improved if you were not of Caucasian stock. Racial, religious, gender and disabled abuse have all joined the bonfire of the unacceptable, as has hate language. Also that pernicious culture of being able to touch women up and, worse, and get away with it is thankfully at an end, though I do wonder if we are right in pursuing old men to the grave. But I acknowledge that justice must trump everything and you could argue that they were lucky to have got away with it for as long as they did before justice finally caught up with them. Finally, while we’re at it, let’s remember that poor unmarried mother whose family once turfed her out. That was not a million miles removed from stoning her.

My point in highlighting all this is to show that Europe in times past – often with us as flag-bearer – has had very backward attitudes. In addition to this we have been exceptionally cruel, physically as well as emotionally. It therefore ill behoves us, as we make progress, to lambast the Muslim world for its tardiness. The whole world hardly needs to take lessons from us in this area. There was a time, which lasted for seven hundred years, when Muslim Spain led the world in virtually all the sciences. While it was rescuing and translating almost all the Greek classics, we were transporting ourselves across the Mediterranean Sea and despoiling their prosperous, peaceable lands in Palestine. Our ‘great’ King Richard (The Lionheart) – who spoke no English and spent only a few months out of his eleven-year reign in England, bankrupting it in the process – wrought such cruelty on Crusade that even today Muslim mothers will quieten their little ones by saying “shhh… King Richard is coming”. He once decapitated 5,000 prisoners on the beach at Acre. Strange it is then that of all our many illustrious monarchs he is the only one honoured with a statue outside Parliament. An unfathomable people we are for making such a judgement. And in terms of cruelty, no Muslim country that I am aware of ever matched our grisly hanging, drawing and quartering routine, nor Bloody Mary’s 300+ burnings at the stake in a five year period, nor Vlad the Impailer’s bestial cruelties, nor the horrors of the 30 Years’ War.

It is very true that we have today a terrible problem – to put it mildly – with certain crazy Muslim men, but we have had our share of crazy men, even if they have not specialised in running wild on the streets with butchers’ knives and Kalashnikovs. The sheer magnitude and level of depraved brutality which our own continent has exhibited throughout the recent century should humble us considerably in our dealings with the rest of humanity. It certainly does not qualify us to hand out advice as though it is coming from on high, and as though we approach the world’s problems with clean hands. However, it is my belief that it is this very barbarism which has made Europe determined to do things differently in the future.

It may not seem so but we are moving into a kinder, more caring world. Not only have we such institutions now as the International Criminal Court, whereby previously unchecked rulers can be held to account, but we show concern and provide help when manmade or natural catastrophe overwhelms one of our brother countries. This is new. Every country now acknowledges that it has a duty to work towards some sort of a welfare state for its people. This, too, is new. Making war without United Nations authorisation is an option becoming increasingly difficult for sovereign states.

Social networking, Skype, emails and the instant availability of facts and information – as well as the next day delivery of goods on eBay and Amazon – makes ours a more joined-up world than it has ever been. And we are only at the beginning. Within three generations, virtually the entire human race will be able to communicate with each other in a universal language. What incredible good fortune that it happens to be our own which will be that medium – and what business opportunities that should present us with if we have the wit to seize them!

Meantime we must hold our nerve as we navigate through what undoubtedly will be treacherous waters, finding ways of containing and then rolling back the bone-headed fanatics who seek excitement on foreign battlefields as well as at home in the misplaced belief that their warped vision is the future. Yet we must do so without compromising our essential liberties and bring our Muslim brothers and sisters on board. Their thinking, young people, in particular, want all the same things we have, including democracy. We must find ways of getting them to prevail over their rogue elements and bring them on board too.

Viva Las Vegas

I’ve always viewed Las Vegas as a totally artificial construct – something dumped in the middle of the desert and catering to the most vulgar, hedonistic, licentious and tasteless leanings of human nature. In many ways it is these things, but in other important ways it is a great deal more.

I’m sitting here in our bedroom on the 28th floor (top) of the 3,626-bedroomed Flamingo hotel close to the 3,933-bedroomed Bellagio hotel as well as opposite the 3,960-bedroomed Caesar’s Palace hotel on Las Vegas’ famous ‘Strip’. What brings me to this exotic location is an invitation from an award-winning San Francisco broadcaster to talk about my recently released book. My wife and I thought it would be an opportunity lost if we didn’t see as many sights as possible of the western US, and Las Vegas is the jumping off place for the Grand Canyon. These three hotels alone, according to our tour driver, have more rooms than all of San Francisco’s put together. Vegas is awash with them and these three represent only the smaller part of an incredible total.

I’ve always viewed Las Vegas as a totally artificial construct – something dumped in the middle of the desert and catering to the most vulgar, hedonistic, licentious and tasteless leanings of human nature. In many ways it is these things, but in other important ways it is a great deal more. My wife and I are not gaming types (never having bought so much as a scratch card or a lottery ticket) and not a nickel slipped through these canny fingers of ours in the three days we have been here. But it is the jumping off place for the Grand Canyon and the Hoover Dam, and it seemed churlish not to explore this ultimate symbol of western decadence and see if we could discover what makes it tick.

To begin at the beginning, I doubt I shall ever again be assigned a bedroom more palatial than the one we have; it has to be more than twice the size of any other we have stayed in. We showed interest in the receptionist who came from Hong Kong and had a little chat. She told us Hong Kongers yearned for the old days and determinedly kept as many symbols and aspects of their colonial past as the Beijing authorities were prepared to countenance (and actually, as it turns out, it’s quite a few). I think our interest and the fact that we were from the old colonial power was rewarded with this magnificent top floor bedroom with its spectacular views. Considering the amazing online deal my wife got, we were truly lucky.

America, as we all know, is a big country and it likes – wherever possible – to do things big. America also works; it’s rare you encounter anything with an ‘Out of Order’ sign on it or malfunctioning in any way. It also does things in style (the showman is never far away) and here you will find everything, absolutely everything: the good, bad and the ugly. The good – and truth to tell there are so many ‘goods’ – is that it is full of so many unexpected delights. One such is a wonderful water course… one is a fountain display in front of the Bellagio hotel the like of which I have never seen. It must be unequalled in the world. Also, no city on earth brings the wonders of electricity so brilliantly to life. An orbiting visitor from outer space would have to wonder what this incredible glow from the blackness of the surrounding desert was all about.

You might say that a fake volcanic eruption in the giant forecourt of one of the strip’s hotels would have to be tacky. But it is not. It is, in fact, a truly breathtaking spectacle and, like the water display, free. There is, of course, much that is vulgar and much that is kitsch, such as Little Venice, but it is a very superior kitsch. Every single structure is built to the highest order using the best materials and the finest craftsmanship. And everywhere is spotlessly clean. Pity the litter-bug Brit who indulges that particular vice of his: he will be jumped on from a very great height. But make no mistake, this place is about money – as much of the lovely stuff as they can legitimately extract, though I have to say they do not harass you. Prices, with some exceptions, are not extortionate. It took a whole half mile of walking to get through one hotel: MGM and its mall. The walk took us past thousands of games machines, umpteen roulette tables, shops, bars and cafes. Any visitor to Vegas needs first to get in training: the walking will test them to their limit, especially those parts under the blazing sun. What a relief that my two knee replacements had bedded in and that I walk the two-mile journey to my shop and back every day.

We visited in the autumn when temperatures are at their best (the high 20s (75F – 80F). But as states go, Nevada is a poor one – close to desperately poor. As a desert state, it has little or no arable land and precious few minerals. Something had to be done. Thankfully it had the mighty, 1,400-mile-long Colorado River, and on it bounty. Las Vegas became possible as did – 400 miles away – Los Angeles. In my own lifetime, Vegas has grown from a few thousand to 2.1m, and it is still growing apace. It is based almost entirely on the service industry. If our excursion driver to the canyon is to be believed, 90% of its workers are on the minimum wage and, irritatingly to those of us from Europe, he made what we would consider an unseemly powerful pitch to be tipped. It is sad that someone has to abase himself in this way to make a decent living, but probably he doesn’t see it that way as he has been doing it so long and has got used to it. The bogeyman in all this is the employer who, by improper means, gains a cheap workforce. But there’s another way of looking at it. America is famous for its service; everybody is keen to help you, to smile at you, to please you. To them we must extend thanks for causing our supermarket checkout girls and others to stop being surly, to engage with us, look us in the eye and smile at us. May this not in part be because their living is not guaranteed and they need your reward for looking after them?

On reflection, it is not so different in my own little shop. I cannot be indifferent to my customers. I must at all times engage with them and provide the service they are looking for. If I and my wife are now celebrating the 20th anniversary of the shop’s opening, may this not be because we have done this? This grim recession has taken its toll. Perhaps 25% of our takings have been lost, but we are still standing and signs are beginning to look up.

But returning to Las Vegas, and how it seeks to please and relieve you of a dime or two, everything operates on a huge scale. The buildings are ginormous with more shiny glass and steel skyscrapers than you are ever likely to see in one place, except perhaps the Gulf States and some newly built Chinese cities. Although much of Vegas is now 40 years old, it looks remarkably pristine and un-weathered. That’s down to the same desert conditions which helped preserves the pharaohs and their monuments. The place heaves with people, but somehow absorbs them so that they do not seem to be too many. There are masses of Malls so that you will still find wide, empty spaces. Las Vegas is America’s premier playground – it’s guilty secret. Running through the country’s psyche is a vein of Puritanism that includes a loathing of gambling. Even now, a majority of the states ban it. It all goes back to those pilgrims who left my own city of Plymouth almost 400 years ago to create a better England, a New England, in a far-off wilderness across the ocean.

Here in the desert, their descendants have conspired to offer a bit of light relief to those earnest hopes of yesteryear. In the process, they have gone a long way to rescuing their basket-case state. Rich widows come here – some regularly – to spend their husband’s fortunes in the cause of cheering themselves up. Ordinary Americans come here because it’s just one helluva place. Executives come here for conventions, naughtiness and show-time on the side. Outsiders like ourselves come to gawk, and newly-weds for the ‘quickie wedding’. From day one the Mafia made it their home and large dollops of their ill gotten gains have been laundered through it and financed its expansion. Hollywood too, along with its stars, once looked down their noses at Las Vegas, but now play court to it. And above it, all the sun shines down for 320 days of the year. It’s an amazing place, and like Muslims with their religious obligation to visit Mecca once in their life, consumerist Westerners should feel a similar obligation to visit this desert El Dorado: this hedonistic, earthly temple of pleasure.

Have the years in Downing Street addled the PM’s brain?

I am glad the government has banned that sinister-looking council vehicle going round with a camera on the top. We all had deep misgivings about Google trundling round photographing everything in sight, but at least that wasn’t a means of filching money out of our ever more depleted pockets and there were many clear positives to the whole operation.

Ours is the most spied on country in the whole world and, to our shame, that includes N. Korea. What is it about those in authority over us that they treat us as they do? Is it that they don’t trust us? They’ll have plausible answers of course – they always do. Not the least of them is that catch-all one of ‘combating terrorism’. But we combated IRA terrorism for thirty years without compromising our essential liberties.

We have to be very careful about going down the path of the surveillance state. The powers-that-be, including the town halls, seem to relish lording it over us – watching our every move, socially engineering us, politically correcting us, and nannying us with a patronising ‘you know it’s all for your own good… don’t get yourself worked up’ sort of attitude. The fact is we are right not to trust them; all the time they are taking liberties with our liberties.

The Cameron government promised more openness. ‘Transparency’ was the word. And all the while the Court of Protection – another Blairite invention – continues on its merry way (except that it isn’t at all merry). Terrible injustices are daily taking place behind closed doors with social workers being treated as if they are expert witnesses and who, in too many cases, are themselves operating behind closed minds. Even the President of the Family Court has expressed his extreme disquiet and called for less secrecy, but still the injustices go on.

David Cameron has called for Magna Carta to be taught to every kid. Is this the same David Cameron who wanted recently, for the very first time in English jurisprudence, to hold a trial so secret that even the very fact that there was to be a trial at all was not to be disclosed? Magna Carta, indeed. Who can forget that cringe-making, toe-curling interview with America’s most famous interviewer, David Letterman, in which the British PM didn’t know what Carta stood for. Eton educated, was he? With a first-class honours degree from Oxford thrown in for good measure? Something went badly wrong there. Even little old me, educated in the Foundling Hospital and at work at fifteen, knew that. Perhaps it is the years in Downing Street that have addled his brain. That hothouse of intrigue and backstabbing must take its toll.

But don’t think me ungracious to our Dave. For all his many deficiencies, he has turned the economy round and we must give him credit for that mighty achievement. There is also a real chance that our kids will stop sliding down the international education league tables and begin the climb northwards. Then there’s that pernicious client state of welfarism that Gordon Brown positively pushed which is being dismantled and a sensible one – such as the Welfare State’s founder, William Beveridge, wanted – being reinstated (but still in a far more generous form than ever he envisaged). So each of these important areas which will determine our nation’s future we must give the present incumbent of Down Street credit for.

A city close to my heart

Although Plymouth has been my home – by choice – now for forty-seven years, there is and will always be another city close to my heart. It is that great throbbing metropolis of London.

I was born there on Grays Inn Road which, on a quiet Sunday, may still be within sound of Bow Bells. If so, that would make me a true Cockney – a born, though not bred, one. Unfortunately the not-bred part renders me incapable of fathoming most of those strange yet endearing Cockney terms.

When I was born in May 1939, London stood on the edge of a cataclysm which would test its metal as much as the plague, the great fire or that earlier fire when Boudicca’s enraged followers torched the Roman city in AD 60. Luckily, when the bombers came, I was safely ensconced forty miles north in the lovely little Essex market town of Saffron Walden. From that area would be assembled the mighty armada of bombers which make good on Churchill’s promise to repay the Luftwaffe with interest tenfold.

When I returned to the city as a sixteen-year-old in 1955 to find a job, it was a sad place. It was not long since its skies had been darkened by Hitler’s bombers. My job was to take news photographs to the art editors of all the leading periodicals and newspapers of the day to see if they were interested in featuring them. The agency was based in Fleet Street. When I stepped out on my rounds I could see the massive structure of St. Paul’s cathedral 500 yards away on the top of Ludgate Hill. To the right and left as you walked up that famous hill was a wasteland of bombed out buildings. Feral cats and other creatures had made the ruins their home. All over Central London, which was my stomping ground, were similar sad sights. I could never quite understand how, amidst such destruction, Wren’s masterpiece had survived. (Later I learned that, apart from an element of luck – which some might prefer to regard as divine intervention – this was because orders had gone out from on high (not that high) that, whatever happened elsewhere, the great cathedral must be saved. The firefighters, therefore, made it their business to prioritise it.)

When I was born, London was the largest city in the world which, perhaps, befitted the world’s largest empire ever. Though today thirty one other cities have overtaken it in numbers, it is still Europe’s largest if you exclude Moscow, which is a Johnny-come-lately having ballooned since the fall of Communism. Before this it was only half London’s size and you needed a permit to go and live there.

When I took up my job, a pall of gloom hung over the city. It was only a decade before that the doodlebugs and V2 rockets had come visiting. We talk of austerity today, but those times knew the real thing: a biting hard period of real deprivation which makes today’s talk sound something of a joke. There was simply not the money to give people a decent life, never mind make good all that bomb damage.

It was a dirty city, too. Those building which had survived were encrusted with a thick, black layer of industrial grime. And the grime was still coming down. Once, I had to get off a bus in Harrow and take my turn to walk in front with a torch to help the driver to avoid mounting the kerb. The smog was so thick you could barely see your feet from a standing position. It was actually quite scary. The dear old Thames, which today is alive with every kind of fish and aquatic creature, was then a dead river.

Unlike Berlin and so many other shattered cities of Europe, London, despite everything, still had a pulse – even a beating heart. But it was weak and its population shrank as so many of its citizens migrated to the leafy suburbs and the new garden cities erected close by. And while all this was going on, the great empire, whose imperial will had reached out from the city across the world, was being disbanded. Truly, it seemed, London’s glory days were over. It would have been a brave pundit who would say it would ever rise again to its former pre-eminence.

Yet hey, that is exactly what has happened. Few would say it was exaggerating to call it the coolest city on the planet. In 2012, with the Olympics, it had the chance to showcase itself like never before in its history. And what a success it made of it. Athletes and visitors alike were stunned at how well that most challenging and complex of events was managed and how beautiful the city had become. Even the sun made a brief appearance, as though to bless our endeavours. London may not exercise hard power to the extent it once did, but it projects soft power by the shedload.

When I treat myself to a visit, as I like to do every three months or so, I look around and marvel at the transformation that has taken place since I trod it walkways as a youth. As its skyline grows ever more interesting, it remains the financial centre of the world, beating New York, Hong Kong and Singapore to the spot. And its many great parks and myriad little squares have grown even more beautiful. Racial bigotry has all but gone, with no more signs to be seen in landlords’ windows saying ‘No Dogs, Irish or Blacks’. Couples of mixed race walk hand in hand and its streets echo to the sound of dozens of languages. Street cafes are everywhere and British cuisine has been turned on its head. It is now right up there with the best. The city has a multiplicity of world-class chefs.

It is at last a truly cosmopolitan place. Not only is the shopping the best to be had anywhere in the world, but, glory be, London now hosts its best fashion houses. Now there’s a surprise for all of us. Perhaps that all began long ago in a non-descript place called Carnaby Street.

So there we have it, my second favourite city. One which, along with our hopefully-reviving economy, we can all celebrate.