Britain’s Role in Shaping the Modern World

Britain has been so lucky. It was perfectly placed for the Industrial Revolution. As an island, it had short lines of communication and transportation with plentiful rivers. Where these were lacking, it dug canals and, forty years later, took trains to the remotest parts of the kingdom. No town or city was more than seventy miles from the sea. Despite its smallness, it had huge reserves of coal and iron. It had displaced despotic kingship with a parliamentary system and had finally become a settled state. Excellent universities worked with inventors and entrepreneurs. Even the factory system and workers turning up at a set time for a set number of hours was their idea. Previously, they had relied on the church bells or a man walking along a street knocking on doors to know the time. Now, thanks to Adam Smith and people like him, they all had affordable timepieces. Hard taskmasters as they were, they were also the first to introduce Bank Holidays.

Commerce was the big driver, even with empire, of which they were often reluctant participants. It even saw itself from the early 19th century as doing God’s work. Its queen, with her dedicated, hardworking German husband, strove to set an example of family life. Is it surprising that before long, they came to believe that the Almighty Himself had appointed them to be a light to the nations? They went out, Bible in hand, to bring the blessings of the scriptures and modernity to distant lands. Their hymns, ‘Jerusalem’ and ‘Greenland’s Icy Mountains’, encapsulate their thinking. All this, and much more, combined with a good business ethos and an all-powerful navy, allowed it to forge ahead to create the world we know today.

How misbegotten it was when I was young to ridicule someone by calling them a Victorian. They were an astonishing breed. However, having said all that I have, any nation blessed with so many advantages would have achieved the same.

Autocracy vs. Democracy: The Stakes in Ukraine

Putin, with a population three times larger than Ukraine’s, plans to expand his armed forces by 170,000. Unable to defeat Ukraine in a fair fight, he seeks to employ the infamous ‘steamroller’ approach that both Stalin and the Tsars relied on: overwhelming numbers. This tactic worked against the plucky Finns in the 1939 ‘Winter War’. They, like the Ukrainians, initially bested the autocrat of their day in spectacular fashion, until the massed ranks of Russia’s poor peasantry were thrown against them.

This time around, the vastly superior ranks of the democracies must ensure a different result. Ukraine absolutely must be supported to the end. Should Trump win the upcoming election and withhold further funding – which I very much doubt – then Europe must step up to the plate. Its resources, both industrial and financial, are twenty times greater than Russia’s, and its population is three times larger.

Should the Ukrainians find their numbers in danger of being overwhelmed – for Russia’s rulers also have historically been careless with their soldiers’ lives – then volunteers from across the continent must step into the breach. Joining the Ukrainian army would not put their respective countries at war with Russia, any more than the International Brigade supporting the Spanish government against fascist insurrectionists put their countries in the firing line. The only reason the democratically elected government lost was that the fascist regimes of Germany and Italy stepped in to aid their fellow fascists.

The Western world must realise that this struggle between autocracy and democracy is one it cannot afford to lose. The consequences of defeat are too dreadful to contemplate. Winning, which must include the recovery of Crimea, may well set in motion the breakup of present-day Russia. It will certainly bring about the fall of Putin. Restive regions with non-Russian majorities may see a once-in-a-lifetime chance to break free. The most likely regions include South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Chechnya, Belarus, Transnistria, and various Siberian Republics. In this scenario, it is entirely possible that a weakened Russia will see the Finns regain the Karelian areas seized by Stalin following ‘The Winter War’, and the Kaliningrad enclave may opt to join the European family.

Unlike at the time of the USSR’s breakup, the democracies must this time embrace the new Russia and help set it on a course that Peter the Great deeply desired for his people: to become true Europeans. Russia has much to offer once it finally turns its back on despotic rulers. The brutal war against a fellow Slav nation, which has shattered the peace of Europe, is increasingly seen by Russians for what it is: one man’s megalomaniac dream of Empire. Empires were a fact of history – if you had the power, you used it, and others, for the most part, went along with it. But they are done and will never return. We, the Portuguese, the Spanish, the Dutch, and the French have all realised this. Only Putin hasn’t.

The Divergent Paths of Angela Kelly and Susan Hussey in the Royal Household

It still rankles with me, the contrasting treatment of Angela Kelly, the late Queen’s dresser, and Susan Hussey, her Lady-in-Waiting. Angela was ousted from her grace-and-favour home on the Windsor estate, while Susan was reinstated posthaste following her unfortunate dismissal. One, a docker’s daughter; the other, an establishment figure – the wife of a former director-general of the BBC.

During the last twenty years of the late Queen’s life, Angela transformed her couturier image from a lacklustre, dare one say, frump-like one to a colourful, stylish one. For that alone, she should have been awarded a Damehood. But more than this, she became such a close companion – enjoying TV and walks together – that the monarch is said to have exclaimed, “We could be sisters.”

Why on earth did the late Queen not anticipate how the establishment would turn on her friend once she was gone and safeguard her future? She knew the nature of the beast that stalked the corridors of her palaces. Despite the awesome position she occupied, the late Queen was of a humble disposition and should have made it impossible for her friend to be treated badly after her passing. I would like to think – though we shall never know, since royal wills are never published – that she left her a few million in gratitude.

From Armistice to Aftermath: Poem for Remembrance

On this Remembrance Day, the 11th of November 2023, we reflect on the armistice that ended the First World War, a day to remember the sacrifices of so many. In 2018 – the centenary of the World War I Armistice – I wrote and posted a poem, but since then, I’ve added two stanzas and modified another. My revisions stem from viewing the two World Wars as essentially one prolonged conflict with a conclusive outcome only in 1945. The same protagonists were involved, with one side refusing to accept its initial defeat, instead preparing during the interwar period for what it considered the rightful outcome in the second.

It was a misstep for the Western Allies to agree to an “Armistice,” a term suggesting a mere truce, at a time when the German army was collapsing, the Hindenburg Line had been breached, and the Kaiser had abdicated. With no path to recovery and its Home Front in revolutionary turmoil, the Allies could have demanded unconditional surrender – and likely would have secured it.

My original poem did not touch upon the second, more devastating round of conflict, nor did it delve into the role of artillery in battlefield losses. The common belief attributes most casualties to bullets, particularly from machine guns, bayonets, poison gas, among other weapons. However, it was in fact artillery – responsible for 60% of the losses – that served as the primary agent of death and injury.

Few war poems capture this immense tragedy comprehensively. I hope my poem does so, portraying the sorrow, waste, and madness of war with poignant clarity. As we commemorate wars past on this solemn day and observe ongoing conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, let us reflect once more on the madness of war.

Echoes from the Trenches

A sea of time has passed us by, and still, we think of them,

The lives unlived, the dreams curtailed, the legions of our men.

We did not know, we could not tell, what horrors lay in store,

As year on year the mournful call went out for more and more.

A maelstrom fell upon our men of iron, steel, and fire,

And sent a piteous wail of grief through every town and shire.

"We must resist," we told ourselves, "the evil, hated Hun,

Have not our leaders deemed this war a just and noble one?"

Through mud and ice and poison gas, the order was ‘stand fast’,

This agony, like none before, it surely could not last.

For four long years, we stood our ground and bravely would not yield,

Till battlegrounds ran red with blood through every poppy field.

Nigh half a thousand miles were dug of trenches where men slept,

Exposed and wet and freezing cold, companionship they kept.

Of lice, of rats, of mice and men, over whom they scurried.

Comes the light, the lice still bite, but off the others hurried.

A wasteland scowled between the lines with not a living thing,

Where even as the dawn came up, the lark, it would not sing.

To cross through no-man’s land and live might be a lucky feat,

But barbed wire and machine-gun fire could yet that luck defeat.

How could men cause such numbing pain and suffering to all?

What thoughts of gain or equity were on their lips to call?

How could they think to justify the carnage and the blood?

What rationale endured to turn their tears into a flood?

Delusions born of hubris' ease had caused them to believe,

This war would be no different from the rest they had conceived.

But science changes everything, and chivalry was dead,

Midst strafing planes and shrapnel shards and mustard gas and lead.

Oh God above, what did man do to vent his foolish spleen,

But sacrifice the best he had on altars of the keen?

How little did he think it through and cry aloud, ‘Enough!’,

But yet preferred to stumble on with bloody blind man’s bluff.

Versailles was born with bitterness and vengeance at its heart,

And so, in barely twenty years, a fresh war would it start.

Depravity beyond belief were hallmarks of this clash,

With millions lost to racial hate, their bodies turned to ash.

Then did at last all Europe rise and vow with every breath,

To put in place a Union to end this dance with death.

A world at war must nevermore be deemed a noble thing,

Its sons and daughters join as one, this anthem now to sing.

Brexit and Beyond: Uniting the Old Commonwealth

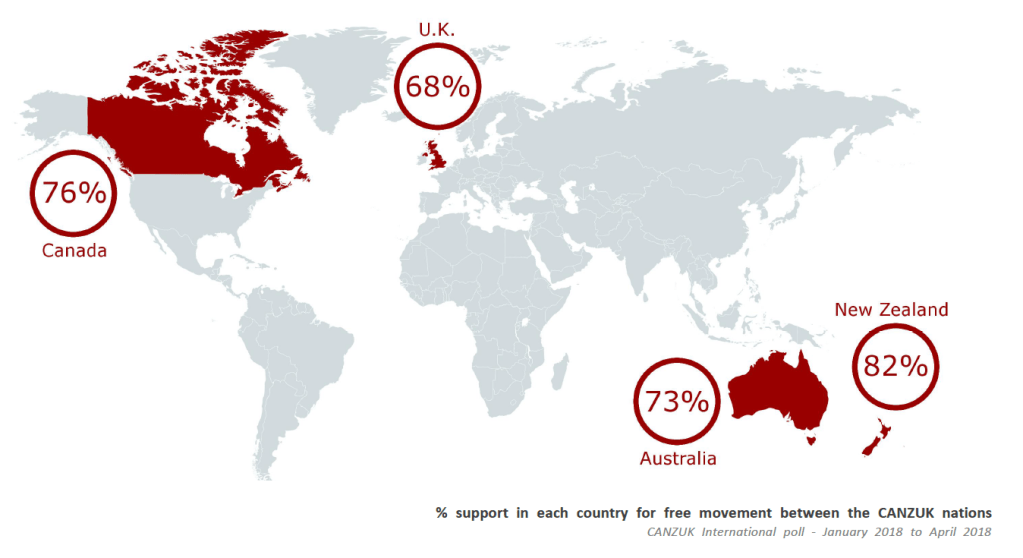

On the seventh anniversary of Brexit, it is both disheartening and exasperating that the project remains shrouded in negativity, with scant attention paid to the opportunities it presents. A dazzling prospect lies in wait for the British government. By overwhelming majorities, the citizens of our erstwhile Commonwealth allies – Canada, Australia, and New Zealand – have signalled their wish for a revival of the kinship that united us at the dawn of the 20th century.

While steadfastly maintaining their sovereign parliaments, these nations envision sharing with us a common defence, security, and foreign policy. They also aspire to enable freedom of movement, commerce, recognition of qualifications, and much more. This collective interest embodies a potential union that could function exceptionally well. Our levels of employment and standard of living are broadly comparable, and almost all aspects of our societal framework; our values, culture, history, parliamentary system, law and language, are remarkably similar. If realised, this would form the largest union globally, and provide a sturdy pillar of support to a beleaguered Uncle Sam.

Objectively, such an endeavour could be considered a straightforward decision and one that should draw cross-party backing. So, why does Westminster hesitate to seize this momentous opportunity? Could Brexit yield a more significant dividend than to reunite our familial ties in such a monumental development? The renewal of this close relationship, now known as CANZUK, holds a promising future.

The emerging power of the CANZUK union

Democracy and our Western way of life are currently in crisis. The rise of a militarised China, a crazed and delinquent Russia, and increasing numbers of authoritarian states pose what some see as an existential threat to our Western values. Yet, a powerful development could potentially reverse this situation.

Forces are gathering for a union of four pivotal democracies – an entity known as CANZUK, an acronym for Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. Public polling indicates broad support: 68% in Britain, 73% in Australia, 76% in Canada, and 82% in New Zealand. Each nation will remain sovereign, yet they’ll cooperate in foreign policy, defence, freedom of movement and trade, recognition of qualifications, and sharing of security concerns—an existing example of such cooperation being the Five Eyes Agreement, which also includes the United States.

In terms of land area, this proposed union would be larger than Russia, boasting a combined GDP of $6.5 trillion and a population of 135 million. Its military budget would exceed $100 billion, making it the third largest in the world.

While many draw parallels between CANZUK and the EU, crucial differences exist. The CANZUK nations share a common language, heritage, and lifestyle. Their standard of living, employment levels, and political institutions run in parallel. Critics of CANZUK have termed it ‘a white man’s club’, but CANZUK International, the organisation advocating for the union, has stressed that the door will remain open to other like-minded nations sharing the same values, including India.

Historically, the CANZUK countries have fought together in defence of freedom, never against each other – unlike the turbulent history of European nations. Another critical difference with the EU is that no CANZUK nation will impose rules and regulations on another, unlike the centralised control from Brussels.

The emergence of the CANZUK union could reinvigorate global leadership, inspire the United States to remain globally engaged, and establish a third significant pillar of Western values alongside the US and EU.

Each CANZUK nation will also gain unique benefits. Canada could negotiate on more equal terms without the overshadowing presence of its giant neighbour. Australia and New Zealand could face China’s assertiveness more confidently, and Britain, once history’s largest empire, would regain its international influence and join the largest confederation on the planet – a reinvigoration sparked by Brexit during its dire straits.

The prosperity of CANZUK members could significantly increase as a result of this union. Critics who question the viability of trade due to geographical distances overlook the success of global trading giants like China and Japan. Advancements in AI and green technology, like the US Navy’s move towards virtually crewless ships, are likely to reduce shipping costs in the future, making the trading prospects even more favourable.

But perhaps the greatest beneficiaries of this promising development will be the young. They would be free to live, travel, study, and work across the expansive regions of CANZUK. Even retirees could benefit from the freedom to relocate. This exciting prospect is, to borrow a popular phrase, ‘a no-brainer.’ It should be for us grown-ups too.

The rise of the CANZUK union could potentially reinvigorate global leadership, inspire the United States to remain globally engaged, and establish a third significant pillar of Western values alongside the US and EU.

While Brexit initially represented a step away from supranational involvement for Britain, it may have ultimately set the stage for a stronger, more aligned union with countries that share deep historical and cultural ties. The post-Brexit era for Britain may not be one of isolation, but of renewed global influence and connectivity.

Many didn’t think Britain had much of a future outside the EU, but the world has always been our oyster. The CANZUK proposal is just one way we’re demonstrating that. Even domestically, we may find a solution to the aspirations of our member nations of the UK. As federal states within the union, they too could at last stand proud as sovereign states.

The notion of poor, tortured Ireland reuniting and choosing to join this new brotherhood of nations is not beyond the realms of possibility. This would be a testament to the appeal and potential of CANZUK, its promise of mutual benefit, and its respect for national sovereignty.

This is not a mere dream; it’s a potential reality within our grasp. It’s time to seize the opportunity and make CANZUK a part of our shared destiny. In an era marked by uncertainty and rapid change, the promise of CANZUK is a beacon of stability and shared prosperity, a testament to what nations can achieve when they unite under common values and a shared vision. Let’s look towards this future with hope and determination.

Unravelling the mysteries of our origins

My followers might have already recognised my profound interest in our own history and that of the world at large. Despite my passion for various scientific ‘ologies’ like cosmology and archaeology, anthropology resonates with me the most.

Experts believe we diverged from our ape predecessors roughly seven to thirteen million years ago. Africa was our primal homeland, teeming with diverse hominoid species traversing its vast stretches.

After several million years on the African continent, some adventurous groups embarked on journeys beyond its confines, marking the beginnings of global colonisation. Approximately forty thousand years ago, four separate groups coexisted: Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and a metre-tall species colloquially referred to as “Hobbits.” However, the latter three disappeared, joining the numerous other hominoids that didn’t survive, leaving us to traverse the vast planet alone.

Interestingly, Eurasians obtained 1 to 2% of their genetic composition from Neanderthals due to interbreeding. The Neanderthals, necessitated by the harsher climate outside of Africa, had developed various immunities, which they passed on to their descendants.

Adapting to the varying environmental conditions from the far north to the south of the planet, these four groups existed uniquely, although it’s possible more remain to be discovered. The lingering, unresolved mystery is why only Homo sapiens have survived until the present day.

Several theories have been proposed, including the possibility of one group’s aggression against another. Given our historical propensity for conflict, this seems plausible. It’s likely our ancestors would have viewed these other groups as lesser beings, possibly driving them to extinction, especially if territorial disputes were involved. We have a historical precedent of such behaviour, as observed in North America, Australia, and elsewhere. However, considering the global resources at the disposal of these small groups, competition was likely minimal. As their numbers increased, there may have been attempts to subjugate them, another unfortunate trait exhibited in human history. All these groups, however, shared an advanced level of intelligence compared to other mammals, providing them an edge in adapting to numerous and varied climatic changes.

Among the four groups, we seemed to be the fastest in developing technology like bows and arrows and intricate stone tools, suggesting a higher intellectual advancement. Possibly, our advanced language skills facilitated more effective communication and strategic planning. Our taller and more athletic physiques would also have made us faster. These abilities likely provided us an advantage in surviving harsher climatic conditions.

Anthropology is riddled with many unanswered questions, and it’s possible that we may never fully uncover some of them. As complex as the mysteries of the universe may be, we seem to have fewer answers to questions about our own origins, making anthropology an incredibly captivating field.

Our Queen impressed all humanity

One day in February 1952 when I was thirteen, a man came into my classroom and said that he had an important announcement to make. “The King is dead,” he said. I cannot remember what else he said before he left, but that day has been fixed in my memory all these seventy years. I had known death before, when my beloved foster father had died when I was three and that sorrowful memory was etched too in my memory, especially when we used to visit that sinking mound of earth which was his grave.

Remembered also was where I was – Fulham Road in London – when I saw the newspaper billboard that announced President Kennedy had been shot. Next was the moon landing during which, in the last frantic seconds before Neil Armstrong descended the ladder on to its surface, I was adjusting the aerial on my home’s roof (I made it in time). Fast forward then twenty-eight years to 1997 and you had my young son at 6.30am on a Sunday morning when I got up early to keep an eye on him telling me that Diana, Princess of Wales, was dead. Finally, you had that surreal image set against a bright blue September sky of the Twin Towers billowing out plumes of blackened smoke, and people leaping from great heights to avoid being burned alive.

Now, the whole world – and not just the British people – stand in shock at sudden death again; not this time of thousands, but of a single individual, our Queen. For almost all of everyone’s lives, she had been a constant presence, almost as though she was one of the stars in the firmament. Now that star had not just faded, but suddenly vanished from the night sky. For seven decades she had been head of a still significant country which even in her grandfather’s time had been the superpower of its age. Just five years earlier, and she would have been Empress of India – albeit briefly – had she come to the throne then. The hard power which it had once exercised had been seamlessly inherited by a former colony which shared identical ambitions. That power valued its old boss’s support in the application of the unavoidable nastiness of hard power.

But Elizabeth’s country then set about the accumulation of massive reserves of soft power, perceiving that to be the only power that works in today’s world and does not garner opprobrium. It had the perfect vehicle to achieve this in the Commonwealth. Three centuries now of the Anglo-Saxon diaspora, with its universal language, setting the world agenda and reordering its workings has brought us to where we are now. All this is not lost on humankind.

Queen Elizabeth II was a very homely person who happened to enjoy – if that’s the word – a very exalted position. She was a shy woman brought up with old-fashioned values. She liked nothing better than that everyone should keep the peace, and that included her own family. She was a gifted mimic who could see the funny side of much that was around her, including pompous people who made a fool of themselves in their efforts to do the right thing in her presence. All of us in doing our job, however much we like it, eventually become jaded, but she never did.

More Scottish than English by ethnicity, she loved the songs of Scotsman Harry Lauder. One of his best known and loved was Keep Right On to the End of the Road. And that is exactly what she did. And this simple fact impressed all humanity.

Soon we shall see the greatest assemblage of its high and mighty that the world has ever witnessed; not for an Alexander or a Nobel Prize Winner who saved humanity from cancer, but for a very ordinary human being with a kind heart. Unnervingly for many, especially the old, we live in a fast- moving world which accelerates by the year, but our Queen seemed to embody those aspects of a lost world which we still pine for and hanker after. Like a permanent fixture for all people everywhere.

Loss

I was on my way to Plymouth Hoe after finishing work for my proverbial cappuccino, feeling down on account of my wife leaving for Lithuania tomorrow. I noticed how the daffodils along the way had given way to the blossom, which is also beginning to give way to the bluebells – each following the other as though designed to keep our spirits up: a challenge for me at this time . A line of verse came into my head linking the two. Over my cappo, it developed into something more. I’d like to share it with you.

You went away at blossom time, The daffs had had their day, But blossom comes to fill the void, Though, briefly does it stay. And then the bluebells swarm about, Its trillions fill the land, Their fragrant scent in woodland parts, Completes this godlike hand. But I am sad beyond recall, For you are gone from me, With no set date for your return, To help me in my grief. I will endure and wait for you, To do what you must do, But beg you in that far off land, To think on me and you.

Whatever Putin’s game plan was, it cannot have been any of this

Recent events still playing out across the distant steppes of Europe are bringing about seismic changes in the geo-political landscape.

Russia, today, stands friendless in a way it has never before. Its leader has unleashed a war that has appalled the whole world and from which there is no easy way to row back without massive loss of face.

Vladimir Putin is a man riven with hatred for what he sees as Russia’s treatment by the West. Too long now in power, he sees enemies in every quarter and has undoubtedly developed a personality disorder which prevents him from acting rationally. So out of touch with reality is he that he actually believed his forces would be greeted as liberators, with flowers tossed on his tanks and armoured carriers. He has convinced himself that a country ruled by a Jewish prime minister and a Jewish president is a fascist state and he calls them Nazis. He invites his countrymen and women to share this outlook.

Galling to him the extreme is that his plans for a quick victory are unravelling and the Western allies uniting to funnel in weapons to enable a protracted struggle to develop.

His choices are stark. Only the application of overwhelming force stands a chance of breaking the logjam. But his soldiers – mainly conscripts – are unhappy. The people they are being asked to kill are what they have always called their little brothers. Unlike in the ‘Great Patriotic War’ Putin’s soldiers are not fighting for their homeland, but to gain possession of another’s. The people they are being asked to despoil are not the brutal, merciless, sadistic Nazis, who regarded them as a lower form of humanity (Untermensch), but fellow Slavs who speak their own language and share a common history.

This time it is not the Russians who are motivated, but their invaded brother nation who, like them in 1941, face an existential struggle for national survival.

Shockwaves have swept across the entire planet which had nurtured the fond belief that a no-holds war of this kind had been consigned to the annals of history. There is a very real risk that million-plus cities will be reduced to rubble. Remembered with melancholy is the fate of Aleppo in Syria and what these same Russians did to the world’s oldest inhabited city.

The entire enterprise has become very personal. Even Hitler did not dispatch death squads to take out his implacable, eventual nemesis, Stalin, as Putin has done with the Ukrainian leader. He is well versed in taking out anyone who seriously offends him, no matter what foreign capital they may live in. The single exception to this is Washington.

Putin’s mindset is one that cannot contemplate defeat, nor tolerate a protracted struggle in which he gets bogged down, nor see his economy wreaked by Western sanctions.

Also, he has unusually sinister plans for the disposal of the dead bodies of his young conscripts. In Afghanistan, even the Soviets returned them to their loved ones which, unfortunately for them, brought home the bitter and melancholy cost of war. Putin is reported to have arranged for mobile crematoriums to be sent to the battlefield. But unlike even the Japanese in WWII, who returned the ashes of their fallen to Tokyo, Putin’s incinerators are designed to vaporise the remains. This is a truly awful man we are talking about.

Notwithstanding the fearful range of weaponry that the Russian tyrant is prepared to use – much of which is banned under international law – this may yet be a war that he cannot win. But if he does, he will need a huge army of occupation since the Western third of Ukraine is ideal partisan country, and Ukraine is Europe’s largest nation – substantially larger in land than France.

Part of Putin’s problem, after twenty-two years in power, is that he is beyond listening to anyone. But there is one power in a position to impose mediation on him and force him to the conference table. That power is China. Apart from a handful of rogue regimes which can offer him nothing, China is the only one which can mitigate, to a degree, the effects of sanctions. It comes to something that he does not even enjoy the support of the mullahs in Tehran.

Such is Putin’s isolation, and so crippling the range of sanctions now deployed against him, that only China can keep him afloat. Putin cannot do without it. As a result, that country is the only one that can twist his arm into a climbdown that may magic up some sort of fig leaf to cover the humiliation involved. It could, perhaps, involve the United Nations.

It may well be that China asserts its power, for the very first time, on the continent which, two centuries ago, began the process of humbling it and bringing it into the modern world. It may broker a conference to bring a halt to the violence presently engulfing the cities and towns of Ukraine.

The truth is that China is appalled at the situation which Putin has brought about. It has an obsession, dating back millennia, in stability. Harmony is in its DNA (providing due respect is shown to its ancient lineage). That doesn’t stop it, however, gloating over the West’s recent disarray with its armies of naval-gazing bleeding hearts bemoaning its perceived sins of the past, as well as the present, and its legions of Woke social justice warriors. These are the kind of warriors that China would like to see more of. It couldn’t believe its luck when it saw the ignominious scuttle from Afghanistan, and the European half of the Western alliance question Uncle Sam’s commitment to Europe. It has revelled even at how its own home-grown virus has laid the Western world low and plunged it into unimaginable debt.

Now, overnight, its erstwhile neighbour, Russia, has inadvertently awoken the sleeping giant of the Free World and both NATO and the European Union are re-energised with the US beathing fire and smoke, and pledging to “defend every inch of NATO territory”. Even pacific Germany has seen the light. It has thrown its mighty engine into rearmament – a terrifying prospect for the Russians – and proposes to take its nuclear plants out of mothballs, fire up its coal-fired plants and free itself from dependency on Russian oil and gas. Nord Stream 2, with its £8 billion dollars of spent investment – much of it Russian – is now for the birds. The formerly proud neutrals of Sweden and Finland are also suddenly keen to join the alliance.

Whatever Putin’s game plan was it cannot have been any of this.

All this means for the Chinese that the long-sought-for seizure of Taiwan is once again off the agenda, for China now believes that it can longer be certain that Uncle Sam will scuttle a second time. Indeed, the landscape has so changed that it seems the entire democratic world is now on the march and its growing dream of a quiescent West standing by while it advances to world domination is now just that: a dream.